Folders |

Backstage With Untold Track and Field History: Bill McClellon Scales Breakthrough Height In San Diego (Second of Two Parts)Published by

Probing the Artifacts ****** From New York To San Diego, Young Bill McClellon Jumps Up, Up And Away By Marc Bloom for DyeStat Part 2 | Part 1 Seven feet here I come? For a time, Bill McClellon seemed to have a love-hate relationship with the 7-foot barrier. Don’t all the greats feel in conflict with “barriers” at some point in their quests? Whether you’re a high school boy trying to break 50 seconds in the 400, or, possibly sometime soon, Sydney McLaughlin trying to break 50 seconds in the 400-meter hurdles, the goal is both a tease and a threat, presenting mixed emotions and a new un-comfort zone. “I thought about it,” McClellon told me, jarring his memory when we spoke at length after more than 50 years. “The press was writing about it. I was just trying to perfect my technique and get stronger.” McClellon was not one to rush things: everything in due course, he said. It was also McClellon’s bent to remember what his beloved grandma Esther had told him: “Don’t get too big for your britches.” McClellon carried humility like sinew. After tearing apart assorted meet, class and national high school high jump records as a DeWitt Clinton sophomore during the 1963-64 season, what could Bill McClellon achieve as a junior? Was 7 feet even possible? Could McClellon find another few inches in his repertoire and at least take a shot at it? McClellon continued training with his team at the Van Cortlandt Park track, for its high jump facility, and running the trails, while getting up to Manhattan College to work with field event specialist Irv Kintsch. “The big thing,” said McClellon, “was to strengthen my legs.” McClellon focused on weight training, but nothing too heavy that might tire his legs: just enough to give him more spring as he leaped to the bar. Coach Charlie Scher’s approach to McClellon’s virtuoso technique — whose elements of motion, force and gravity would have made for an inspiring Clinton science project — was to remain hands off. “I just leave him alone,” he told one reporter. “Do you blame me?” When McClellon returned to the Bishop Loughlin Games for the start of the 1964-65 indoor campaign at the New York Armory — then called 102nd Engineers Armory — his national indoor record stood at 6-8. His outdoor best, 6-8.50, stood as the national sophomore record. The high school outdoor record was 6-10.50 set by a California boy, Max Lowe of Mountain View, the previous spring. Was there anyone around to give McClellon some competition? Karl Kremser, his former rival from the Philadelphia suburbs, had entered West Point after winning the Pennsylvania state outdoor title as a senior. Kremser continued using the straddle in competition for the Cadets and would eventually make his mark on the national scene, in more ways than one.

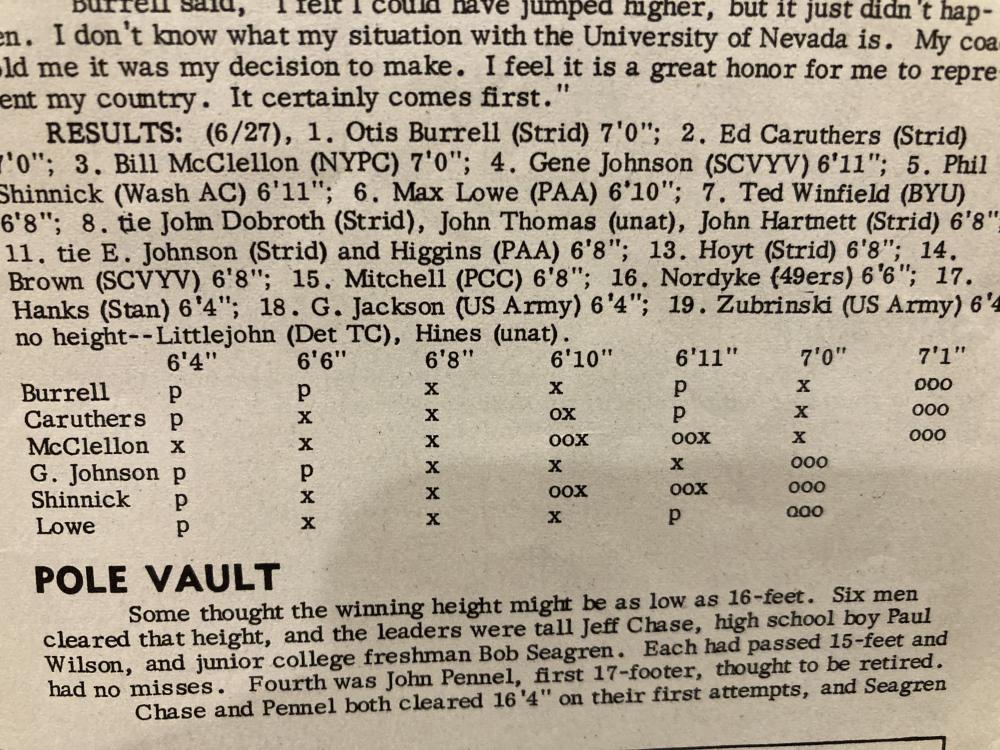

McClellon came out of the blocks flying. He won the Loughlin Games in 6-9.50, breaking his national indoor record. He went nine jumps without a miss, was flawless at his winning height and took three attempts at 6-10.50. Six weeks later, in January, McClellon won the St. Francis Prep Games in 6-10.25, another national mark, and best in Armory history by anyone including collegians and open jumpers. McClellon missed two attempts at 6-11.25 and passed on his third. The competition had started at 10 a.m. and ended at 3:20 p.m. He could now “see” 7 feet but was bushed, saying then, “I was too tired for that last try. My goal is 7 feet but I’m not sure I could make it this year.” I was one of those “press” people bugging McClellon about 7 feet. I was now 18, and in college, with a year of reporting under my belt. I was working on my interviewing skills. McClellon, at 17, was usually free with his comments. With his international experience in London six months earlier, McClellon carried himself like an Armory pillar, a young athlete who could control his event with peerless certitude, standing out even among his contemporary Armory legends like John Carlos and Vincent Matthews, Julio Meade and Otis Hill, James Jackson and Mark Ferrell. At the St. Francis meet, with his Clinton gear in the laundry, McClellon wore his AAU uniform from the ’64 London trip as a badge of honor. He also had 7’ 2” taped to his back, his stated goal for 1966 — his senior year. In that touch of boldness, McClellon reflected what city coaches of the era taught: take the lessons of the neighborhood, the street vibe that spoke to you — as immortalized in the work of another Harlem habitue’ and DeWitt Clinton alum, James Baldwin, whose mid-50s classic “Notes of a Native Son,” served up poetic license to the disenfranchised — and bring that vitality and backbone into the building, where any lapse in command could yield defeat. With the risk of a misstep in timing from run-up to take-off to control of arms, legs and torso over the bar, the straddle was a delicate dance with little wiggle room. That spring, my cub reporter learning curve merged with McClellon’s next big jump, erroneously called a “national outdoor record” of 6-10 (statisticians didn’t know the status of the Lowe jump then) at the PSAL championships on June 4, 1965, at Randalls Island. T&FN published my PSAL story verbatim. It might have been my first byline. The “lede”: “New York City, June 4 — William McClellon, only an 11th grader at DeWitt Clinton High School, turned astronaut here today and now qualifies as the sole claimant to the national prep high jump standard.” How’s that for some classy sports writing? I went on to detail how McClellon nailed every bar until 6-10, which he cleared on his third attempt “with inches to spare,” and then took three tries at 7 feet (his first tries ever) without success. Asked about those final misses, McClellon told me in our talks that at the time he felt down on himself, sulking, “Maybe I’m not ‘supposed’ to clear 7 feet.” It must have been a temporary teen-age sulk. McClellon emerged from the meet with a streak of 28 straight high jump victories — indoors and outdoors for two years — that he was not even aware of, and with a resolute attitude toward 7 feet: “It’ll come when it comes.” (When months later the aforementioned Max Lowe’s 6-10.50 jump from ’64 was discovered by T&FN — Pony Express was our media ecosystem — my references to McClellon’s 6-10 “national record” in June ’65 would prove incorrect. The T&FN omission was soon corrected in its hundred-deep all-time list of performances at the end of the year.) Remarkably, one week after McClellon’s PSAL 6-10, he returned to Randalls Island for the Eastern States Championship and jumped 6-10.50 to equal Lowe’s jump. At the same meet, Bob Beamon, from Jamaica High in Queens, flew 25-6.75 (wind-aided) and 25-3.50 (legal) in the long jump. Ironically, even though I could vividly recall standing at the end of the long jump pit thrilling to Beamon’s attempts (he would also set a high school record in the triple jump the next week at the Golden West in Sacramento, soaring 50-0.75, the first schoolboy 50-footer), I had no recollection of McClellon’s performance; and, in our reminiscences, he neglected to bring it up. (It took a reminder from historian/statistician Jack Pfeifer, president of the Track & Field Writers of America, to revive my ’65 Easterns’ memory.) With his 6-10 and 6-10.50 jumps, McClellon qualified for the National AAU Championships, two weeks later at Balboa Stadium in San Diego. When McClellon packed his bags and set out with his club team, New York Pioneers, his mates included Beamon and Carlos. McClellon took on the nationals as another day at the office — er, the Armory: stay focused, tune out the noise, master your technique and make your team proud. McClellon told me that being an only child enforced an independence that he carried with him to the big meets and beyond. “Even to this day,” he said. “Traits I picked up as a child, to do things when they need to be done.” His Clinton teammates took notice. “We were in awe of Bill’s maturity,” said Kenny Anderson, who shared captain duties with McClellon in their senior year. “That was the big difference between Bill and everyone else.” In San Diego, virtually the entire AAU field was made up of West Coast jumpers, and McClellon was pretty much alone in coping with travel fatigue and time zone changes. It was his first meeting with John Thomas, who was injured and only made 6-8. Perhaps it was more than symbolic that Lowe, by then the junior college record holder at 7-1, would finish sixth, making 6-10, passing at 6-11 and missing three times at 7 feet. Also left behind, in fifth place, was Phil Shinnick, a 1964 Olympian in the long jump who in 1963 set a controversial world record of 27-4 (he was not given credit for it until 2021, 58 years later, because of a wind gauge issue), and would go on to earn a Ph. D from Berkeley and become a college professor and peace activist. Shinnick, a versatile athlete, cleared 6-11 on his third try before missing three attempts at 7 feet. The field featured another ’64 Olympian, Ed Caruthers, as well as Burrell, by then at the University of Nevada. Caruthers would go on to take the silver medal behind Dick Fosbury at the Mexico City Games in 1968, achieving a lifetime best of 7-3.50, a year after winning the Pan Am Games and being ranked number-1 in the world. Burrell did not make it to Tokyo the prior year but had recently posted the best American jump of the season, 7-1.75, in an international meet in Poland. Burrell had been a consistent 7-footer for three years with a jumping style that McClellon found odd. Burrell would start his run-up very slowly, then speed up his last three strides to the bar, hurling himself over with a straight-leg kick. I asked Burrell about his style when I reached him in Los Angeles, where, at 78, he serves as a part-time jumps coach at Torrance High School, once used as a backdrop for the 1990s hit TV series, “Beverly Hills 90210.” Burrell was probably the favorite in San Diego coming off his AAU indoor victory in Detroit at 7 feet. He said he purposely “stayed on the ground longer” in his take-off, which McClellon suggested to me might have been a mind game to psych out the opposition with a showy confidence. In high school, Burrell said, he was uncoordinated, hardly good promise for a high jumper. Stuck at 5-5 to 5-9 as a sophomore, a change in Burrell’s right arm position resulted in him jumping a full foot higher, and tying for the California state title. Burrell finished his high school career at 6-9.50, in 1962, close to the national record. With the primitive communications apparatus of the time, McClellon knew nothing of his opposition. His main challenge was fatigue, waiting between jumps, and never feeling like his body was operating on local time. McClellon estimated that from start to finish, at least a hundred jumps were taken. The opening height was 6-4. Burrell, Caruthers and McClellon were among six jumpers who cleared 6-8 on their first attempts. Burrell and Caruthers seemed to be playing it cute. Burrell made 6-10 on his first attempt; then he passed at 6-11. Caruthers made 6-10 on his second attempt; then he, too, passed at 6-11. McClellon took all three tries to make 6-10 and 6-11. Via clearances or passes, the top six competitors were all in when the bar was raised to 7 feet. While the high jump was one of the best competitions of the two-day meet, it was far overshadowed by two of the most memorable races in track history — 18-year-old Jim Ryun’s American record 3:55.3 mile victory over three-time Olympic champion Peter Snell of New Zealand, and the virtual dead heat six-mile world record of 27:11.6 run by 19-year-old Gerry Lindgren and ’64 Olympic 10,000 champion Billy Mills. The meet’s top performers were eligible for the American team competing in the annual U.S.-Soviet Union dual meet in July.

It was McClellon’s turn. He took position on the right side, embarked on his temperate approach, leaped and curled over with his fisted left arm extended and trailing leg well above the bar Mondo-like for a clearance. On June 27, 1965, Bill McClellon achieved the first high school 7-footer. It was witnessed by a Balboa Stadium crowd of 15,320. One month later the Beatles played Balboa. The crowd was 17,013. After his two-year succession of record-breaking performances in the frenetic urban milieu of New York, it was perhaps ironic that the young man from Harlem, first nurtured in the wide open spaces of the Piedmont, then funneled into a school for troubled youth, emerging with manliness at a military installation in swinging Washington Heights, would wind up recording his iconic jump in a place known for its beaches, golf, sunshine and surfing. At the time, the 1960s turbulence, controversy and cultural liberation were in full flight, but seemingly with minimal impact in “surfin’ safari” San Diego. The Selma-to-Montgomery “Bloody Sunday” civil rights march had been staged weeks earlier in Alabama. The Vietnam War was raging. And Bob Dylan came out of Greenwich Village with his signature hit, “Like a Rolling Stone,” with its penetrating lyric that would become a touchstone of the generation: How does it feel? McClellon had an answer regarding his historic jump. “So many people were asking me about it. It was like a load off my mind,” McClellon told me. “But I had to get over that and move on. I had no time to get overjoyed because they moved the bar to 7-1.” Burrell, Caruthers and McClellon all missed their three attempts at 7-1. “I had two good ones,” McClellon recalled, “but fatigue is always a problem at the end.” Based on misses, Burrell was declared the winner, the first of four AAU outdoor titles he would collect, with Caruthers second and McClellon third. McClellon called coach Scher in New York with the news, and Scher passed the word around. What would McClellon do for an encore? He would jump 7 feet again. On July 15, the Pioneers made their annual trip to Buffalo for the Firefighters meet. Lethargic from all the traveling, McClellon took three tries to duplicate his San Diego performance while defeating John Thomas again. At the time, Thomas, probably past his prime, was the American record holder at 7-3.75, set in 1960, when that mark was the world record. His Soviet rival, Valeriy Brumel, now held the world record at 7-5.75”. McClellon discerned that both Brumel and Thomas were “speed jumpers with a straight-leg drive,” as opposed to his more deliberate style. Today, McClellon’s pride reflects his world view that it’s the effort that is most meaningful, more so than the final product. “The mere fact of preparing stays with me as I continue to live my life,” he said. He brought up the trips to Van Cortlandt, tackling the trails like a cross-country runner, building endurance for the long competitions, for jump after jump, with no margin for error. “I’ve always felt,” he said, “there’s nothing I can’t do with the right frame of mind.” After Buffalo, 10 days hence, McClellon would affirm that sureness again. He was back at Randalls Island in a tune-up meet for select Americans soon to compete abroad for the U.S. in the Soviet Union and Europe. While McClellon’s AAU third-place had not earned him a berth on that summer’s squad, he won the high jump that day in 6-10 while defeating Caruthers, the AAU runner-up, and the other “pros.” McClellon’s participation was almost an afterthought. With his ticklish teen-age interests, he was able to pick up the high jump and put it down whenever he wanted. A New York Times story, commenting on McClellon’s victory, marveled, “And he did it without practice for a week because he was on vacation.” That’s what McClellon had told the reporter: on vacation. Bill was sweet on a young lady from the Bronx, who attended Evander Childs High School, not far from Clinton. They’d met in church. On his “vacation,” Bill and his girl went to Coney Island, Jones Beach, Palisades Park, or just hung out at her house, which was more spacious than Bill’s Harlem flat. It was a Bronx tale: “A Teenager in Love,” the soundtrack of the street corners, courtesy of Dion and the Belmonts, the borough’s favorite sons, serenading girls with tall hair and guys in black leather jackets, plus a certain high jumper and his sweetheart. When his respite was over, McClellon not only had his senior year to look forward to, but an international trip of his own. The U.S. assigned him to compete in October in an indoor meet in, of all places, Sao Paulo, Brazil. The American contingent featured California pole vault roommates John Pennell (who would become a four-time world record holder) and Bob Seagren (who would capture the 1968 Olympic gold medal), along with the AAU high jump champion Burrell, already a veteran of many U.S. international trips. Over the summer, Burrell had won five of six meets on a European tour of six nations, finishing the season ranked fourth in the world. McClellon, just turned 18, traveled alone from New York, practically an all-day adventure. No AAU officials accompanied him. On a connection in Caracas, Venezuela, he lost his wallet, later found just before departure. Once in Sao Paulo, he barely had time to put on his AAU threads to compete. Burrell and McClellon took second and third with jumps of 6’ 11 1/8”. (The winner was a German named Shillkowski.) McClellon’s mark, later lowered to 6-11 when measurement in eighths was done away with, had broken his high school indoor record set the previous January at the Armory. In total, McClellon had broken the high school indoor record five times, and the outdoor record once plus two ties, eight records in all, in a little more than a year. Next day he flew home and was back in school. McClellon’s future could not have been brighter. His last six jumps, from the PSAL meet, Eastern States, National AAU, Buffalo, U.S. tune-up and Sao Paulo: 6-10, 6-10.50, 7-0, 7-0, 6-10 and 6-11, including the virtual tie for the national title and international credits. Only two American jumpers of 1965 (Burrell and John Dobroth), and seven jumpers worldwide, had a better resume. McClellon was clearly the greatest high school jumper of the pre-flop era, and possibly of all-time. If you skip ahead five years to 1971, with the advantageous Flop all the rage, the nation’s leading high jumper was future Olympic medalist Dwight Stones, who that season had three jumps over 7 feet with a best of 7-1.50, plus two more at 6-11 and 6-10.25. That same year indoors Stones led the nation at 6-10. If you look at last year’s indoor season (56 years later!), only three jumpers cleared 7 feet and only two more cleared 6-9. (The current high school records are 7-7 outdoors and 7-5.25 indoors.) At Clinton, athletes in other sports did not quite appreciate McClellon’s skills until one day when he was walking through the gym and the basketball team challenged him to a dunk contest. The 5-11 McClellon floated up well above the rim as much taller players with lesser dunks watched in awe. McClellon’s senior year, however, was practically a wash-out. A right knee injury he attributed to “all the jumping” sidelined him. Busy receiving chiropractic care (as he was assessed “out of alignment”) and visiting college campuses, McClellon managed to win the PSAL indoor meet in 1966 in 6-7.75, barely higher than his ’64 novice emergence. He found even less success in his few outdoor meets, suffering a couple of losses. Meanwhile, a second boy, from California, jumped 7 feet and another high schooler, from Texas, moved the record to 7-0.25. After high school, McClellon’s life took some challenging twists and turns, but his resourcefulness always paid off for him. In the fall of 1966, he entered Southern University in Baton Rouge, La., a historically black institution with an outstanding track team under Coach Dick Hill. While getting used to the South, and its racial strife, McClellon jumped 6-10 as a freshman, picked up a couple of wins and added the triple jump to his agenda for team points, leaping over 50 feet. In a mix-up following his decision after two years to transfer from Southern to Abilene Christian in Texas, McClellon’s college deferment fell through the cracks and he received a draft notice from the army. Instead, McClellon chose to enlist in the Air Force as a better next step in life. McClellon would spend 25 years, from 1970 through 1994, in the service. During this period, stationed throughout the U.S. and in West Germany and the Philippines, he finished his college education at Abilene Christian, while winning the NAIA indoor triple jump title at 32; took an additional program to earn a degree in orthopedic technology, his job in the Air Force and career path afterwards; and got married in California to his wife of now 45 years. While in Germany for four years at Bitburg Air Force Base, a front-line NATO base during the Cold War, McClellon participated frequently in inter-service meets with other U.S. base teams in Europe, competing in several events and achieving lifetime bests in the triple jump of 52-2 and long jump of 24-6. McClellon was present at Bitburg during Pres. Ronald Reagan’s controversial visit to a Bitburg cemetery commemorating the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II, apparently not realizing that some of the buried soldiers had been Nazi criminals who’d murdered innocent victims by the thousands. While McClellon never saw combat in the military, his life came under threat in the Philippines, during the 1991 violent burst of the Mount Pinatubo volcano, the world’s largest volcanic eruption of the prior 100 years. McClellon was stationed at Clark Air Base, on Luzon Island, and serving in his orthopedic capacity, working with doctors and other medical personnel. More than 800 people died with thousands more injured. Amid the evacuation of more than 250,000 people, including U.S. military, and much of Clark base destroyed, McClellon and his orthopedic surgeon partner stayed behind, imperiled, while caring for the wounded. “It was raining mud,” he recalled. Once retired from the Air Force, McClellon and his family settled in Dayton, Ohio, where he had once been stationed at Wright Patterson Air Force Base. McClellon continued his orthopedic work at Dayton Children’s Hospital, retiring about a year ago. Occasionally he would put on a pair of old shoes and high jump at a school track. Five years ago, at 70, he said, he cleared 5-5 on no training. The men’s world record for a jumper 75 and up is 4-10.50. The 2022 USA masters’ 75-79 champion, competing recently in Lexington, Ky., jumped 4-3.25.

Most of the straddlers shied away from the Flop when it came into practice. Some couldn’t learn it. Others feared it. “I always wondered how these guys kept from breaking their necks,” said Kremser. McClellon held it in low regard, like something of a gimmick. Considering the fundamentals that changed his life, McClellon was wedded to his first musical notes, the ones that led him to sing and soar. “The Flop resembled a somersault,” he said dismissively. “It turned a lot of 6-7 jumpers into 7-footers.” Just as McClellon competed in field events later in life, Kremser competed in the field, too — the football field. Tennessee coaches realized they had a potential place-kicker in their locker room. Kremser became one of those “soccer-style” kickers of the era, lofting an SEC record 54-yard field goal to help the Vols defeat Alabama in 1968. Kremser never got a track scholarship, only for football. Finishing college, Kremser was a fifth-round draft pick of the NFL Miami Dolphins. He played a little more than a year before being cut. After that, Kremser took on various teaching and coaching positions before being named men’s head soccer coach at Florida International University, where Kremser spent 27 years earning national distinction, before retiring in 2007. Soccer had been among his first sports in high school. After Nevada, Burrell, whose lifetime best is 7-2.25, kept jumping around the world, ultimately in more than 50 countries. One trip could be a story in itself — in 1969 to Southeast Asia. Arranged by the state department as a goodwill mission during the height of the Vietnam War, Burrell, in a contingent including sub-4:00 miler John Mason and world record 110 hurdler Earl McCullough, conducted clinics for local athletes in Burma, Thailand, Taiwan, South Korea and, yes, Vietnam. “There were rockets and mortar exploding all night,” he said. “I slept on the floor.” Burrell, at 78, still jumps in Senior Games events, doing 4 feet and change — with the straddle. McClellon vowed to get back into training. He now takes seven steps to the bar, not five. “I’ve adapted,” he said. McClellon also now jumps from the left side, the result of a right meniscus tear he incurred jumping in the Air Force that was surgically repaired, enabling him to continue competition. McClellon, at close to his high school weight, thinks he’s still got a 6-foot jump in his legs and is hoping to travel to masters meets next year. Could the first high school 7-footer also become the first 75-year-old to high jump 6 feet, or even 5 feet, in a national event to come? If McClellon’s attempt comes to pass, Karl Kremser will be rooting for him. “Whenever I think of Bill McClellon even today,” he said, recalling their high school competitions that proved to be the foundation of the first 7-footer, “I think of his wide smile, his grin from ear to ear. Bill was the nicest guy.” #

Marc Bloom’s personal reflections on track and field history appear periodically. His last story can be found here. Marc’s latest book, “Amazing Racers: The Story of America’s Greatest Running Team and its Revolutionary Coach,” about the Fayetteville-Manlius cross-country dynasty, was named 2020 Book of the Year by the Track & Field Writers of America.

More news |

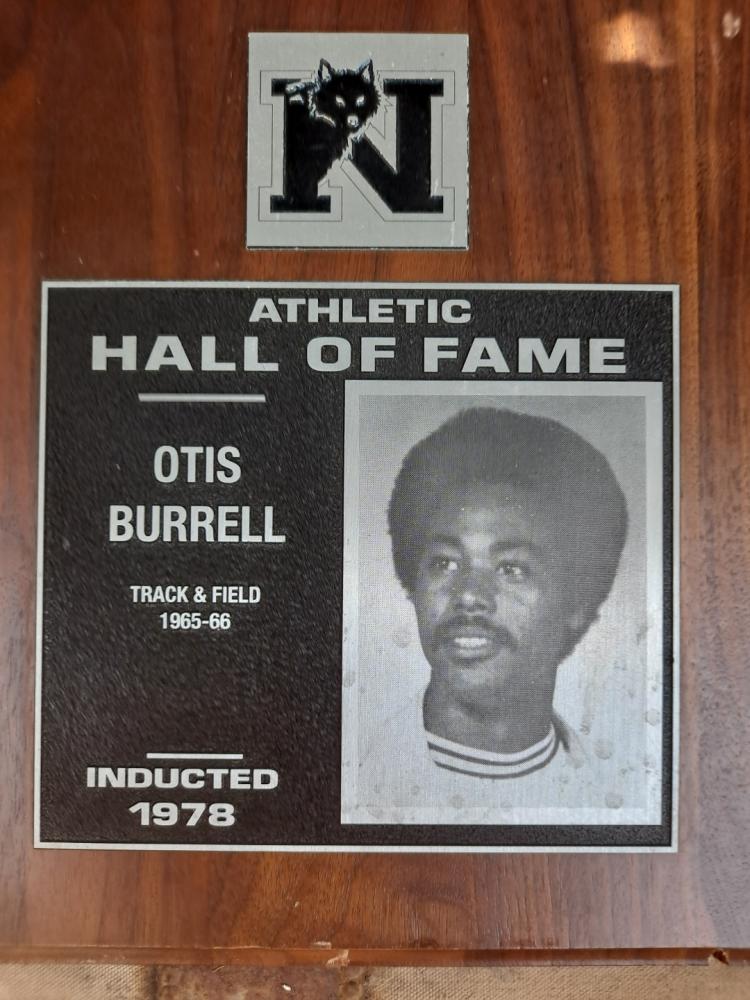

Another up-and-coming jumper, Otis Burrell of southern California, was setting the stage for future American dominance with a 7-foot leap at L. A. Valley College, a two-year school, becoming the ninth man ever to clear that height, in 1963. Burrell had attended Jefferson High in L. A., the same school as Charlie Dumas (who later transferred to Centennial Compton), the first man, in 1956, to jump 7 feet. Dumas was to the high jump (with slightly less fanfare), as Roger Bannister was to the mile, two years earlier.

Another up-and-coming jumper, Otis Burrell of southern California, was setting the stage for future American dominance with a 7-foot leap at L. A. Valley College, a two-year school, becoming the ninth man ever to clear that height, in 1963. Burrell had attended Jefferson High in L. A., the same school as Charlie Dumas (who later transferred to Centennial Compton), the first man, in 1956, to jump 7 feet. Dumas was to the high jump (with slightly less fanfare), as Roger Bannister was to the mile, two years earlier. As he jumped, McClellon was unaware of the heroics on the track. History awaited him, too. The bar was moved to 7 feet. Burrell cleared on his first attempt. Caruthers did as well. Shinnick, Lowe and Gene Johnson were all out on misses.

As he jumped, McClellon was unaware of the heroics on the track. History awaited him, too. The bar was moved to 7 feet. Burrell cleared on his first attempt. Caruthers did as well. Shinnick, Lowe and Gene Johnson were all out on misses. McClellon’s old rival, Karl Kremser, 76, had no such aspirations, as he recounted to me from his retirement perch in the Florida Keys. Like McClellon, he, too, transferred college after two years. Lacking the qualities of “a model cadet,” as he put it, Kremser left Army for Tennessee, where he became a model Volunteer, winning the SEC indoor and outdoor high jumps and placing second to Fosbury in the 1968 NCAA championships at Berkeley, where he cleared a lifetime best of 7-1. Three months later, the Fosbury Flop would change the high jump forever.

McClellon’s old rival, Karl Kremser, 76, had no such aspirations, as he recounted to me from his retirement perch in the Florida Keys. Like McClellon, he, too, transferred college after two years. Lacking the qualities of “a model cadet,” as he put it, Kremser left Army for Tennessee, where he became a model Volunteer, winning the SEC indoor and outdoor high jumps and placing second to Fosbury in the 1968 NCAA championships at Berkeley, where he cleared a lifetime best of 7-1. Three months later, the Fosbury Flop would change the high jump forever.