Folders |

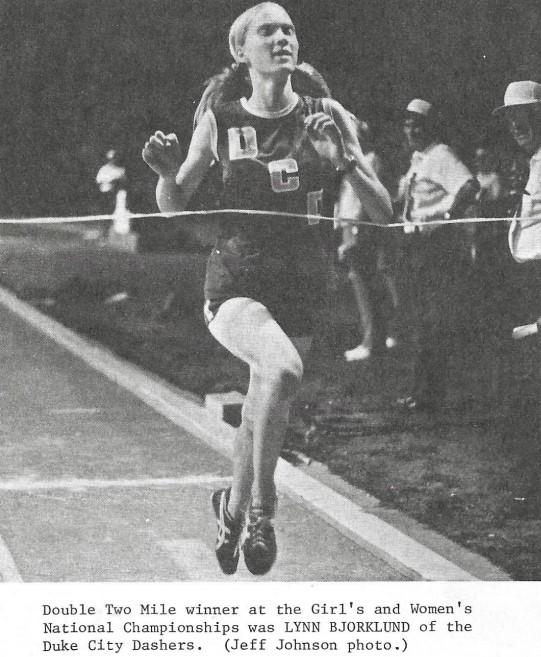

Part 2 of 2: Lynn Bjorklund's Prodigious Talent Takes Her Behind Iron CurtainPublished by

Backstage With Untold Track and Field History ****** Teen Sensation Finds Favor Abroad While Leading U.S. Team By Marc Bloom for DyeStat Part 2 | Part 1

Lynn Bjorklund, 18, 1975 AAU 3,000-meter champion in a high school record 9:10.6, and the other women’s qualifiers for the annual U.S. vs. USSR dual meet, were rushed from the White Plains (N.Y.) nationals into a Manhattan hotel for departure to Kyiv with the American squad. “We were so naïve,” said Cindy Bremser, the second 3,000 qualifier, who roomed with Lynn. “It was like, ‘Guess what? You just made a U.S. team for overseas. Get packing.’” A USA uniform and free bag — oh, the joy! The women had no passports but officials provided them within 24 hours. Bjorklund and Bremser hit it off. Bremser, then 22, was one of the first collegiate female varsity runners, starting to compete in her junior year, on the heels of Title IX, at the University of Wisconsin in 1973. “I needed the exercise,” she told me. The ground-breaking roomies were shy, but not when it came to their running. They were itching for a break-the-ice workout the night before the trip but team officials forbade them from leaving the hotel and going out into New York City streets without chaperones. Plan B: they ran up and down the hotel stairwells. While Lynn’s eating and weight issues had injuries knocking at her door — and were easy to hide from roommates as well as family — for Bremser the trip was a stepping stone to future worldwide success: Pan American Games 1500 silver in 1983 in Caracas. Weltklasse runner-up 3,000 silver in Zurich in an 8:38.60 PR in 1984. World Cup 3,000 bronze in Canberra, Australia in 1985. Goodwill Games 5,000 bronze in Moscow in 1986. In ’84, Bremser came within a half-second of an Olympic medal in the Mary Decker-Zola Budd 3,000 fiasco at Los Angeles. From behind, Bremser had a front row seat to the collision, which led to the victory by Maricica Puică of Romania, as Bremser wound up fourth. (It was the first women’s Olympic 3,000, and of course the first marathon, won by Joan Benoit Samuelson.) With the shoulders of a swimmer, Puică drew suspicion, given the growing talk of drug use among women within the Soviet bloc. After the Games, when Bremser gave a school talk and showed the race video, one student, she said, piped up and asked, “Why did you run against a man?”

To refer to sporting contests in today’s embattled Kyiv, at this moment in history, a year into the Russian war, is to feel shattered by the clash of civilizations. Indeed, it was only three months before the ’75 meet that the Vietnam War had officially ended, a war ostensibly fought over the spread of communism. And here was the unassuming teenager from the city that fashioned the bombs to fight our enemies lining up against women with big shoulders from the evil empire. Funny thing though, Bjorklund found joy in meeting the ordinary people on the other side of the Cold War. She had taken classes in Russian language at school and walked around Kyiv like a U.S. team emissary and peacemaker greeting people in Russian, saying, “Hi, my name is Lynn. Who are you?” Lynn’s rare openness endeared her to the locals, so much so that she felt refreshed with not being judged, finally liked for who she was. Men and women on the street had no idea Lynn would soon run perhaps the greatest distance race by an American teenager. As if all this was not enough irony, the meet was held on July 4 weekend. Lynn’s family back in Los Alamos settled in around their TV for the live broadcast, an annual summer must for track fans. Lynn’s mountain runs were still her calling card. Could those New York stairwell spurts have added some polish? On July 5, as the race got under way, Bjorklund took the lead and held it. “I had to run that way,” she recalled. “I had no kick.” That’s how it went for seven laps. With 200 to go, Bjorklund, still ahead, dug into her Jemez dominion, all she’d accrued from the canyons and mesas and pulls up the grueling ascent, and on the home straight appeared headed for certain victory — the aesthete with “biomechanical issues,” as Ric Rojas put it. She was poised to “beat the Russians,” no honor greater in the cosmic sporting landscape (think “Miracle on Ice”, 1980) when… Bjorklund misjudged the finish line and came to a dead stop! Realizing her mistake, she re-started like a car with a dying battery as two women swept by her. First place, Rositsa Pekhivanova of Bulgaria (U.S. officials called last-minute Bulgarian entries “a cute Soviet trick”), age 20, 9:07.4. Second place, Svetlana Ulmasova, Uzbekistan of the USSR, 22, future European champion and world record holder (8:27.68), 9:08.4. And then: Third place, Lynn Bjorklund, USA and Duke City Dashers, just turned 18, 9:08.6 — an American record, American junior record and U.S. high school record, improving upon her recent 9:10.6 in White Plains. The high school mark would stand for 41 years, the longest of any girl’s track performance. Bjorklund’s miscue, costing her the win and a faster time, was tragic but only for those keen on material reward. Lynn shrugged it off, then and now, aloof to the stats, while her family, huddled at the TV, watched with pride and, recalled Mark, “celebrated in a quiet way.” When we spoke, Lynn could remember little about her record race, but much about everything else: how the team’s distance athletes were reprimanded by authorities for venturing into the Kyiv countryside on a run; how she and Cindy wondered whether their room was bugged; how on a layover in Paris, Americans were caught stealing hotel towels; and how one of the athletes got into a fistfight with a waiter, er, garcon. She spoke mostly about the Russian people and their delight over her language skills — this was no ugly American, we love you. On the street, citizens wanted to buy the jeans she wore and the shirt off her back. At an athletes’ dinner, Russian coaches offered advice on her form (over-striding, etc.) and pointed her out, as if she were one of theirs.

The mystery of the urn endures. No one told Bjorklund why she received it, whether it was given spontaneously, or planned, and if so, for what reason? Bjorklund was not an event winner; she held no distinction other than her modest Russian tongue. Maybe that was enough. Maybe she was considered the charge’ d’affaires. The boss lady. Three days later in Prague, against Poland and Czechoslovakia, Bjorklund took ill, ran sick for team points and placed third in 9:25.0. Bremser collected her first international triumph in 9:21.8 and was awarded a lovely teapot (see photo), akin to the urn, which she, too, displays. Lynn’s points mattered as the U.S. women defeated Poland by six points, and the Czechs by 18. (Both U.S. men and women, not at full strength, got swamped in the Russian meet.) Back in the States, in Durham, North Carolina, for the third and final leg of international events — versus West Germany and a Pan African team — Bjorklund, her illness gone, placed second by a stride to a German in 9:12.6. From junior and senior nationals to the trio of U.S. team meets, it was a whirlwind 24 days with five 3,000-meter races for Bjorklund. Her best times, 9:08.6, 9:10.6 and 9:12.6, while historic for American youth, went down with expectation in Los After 47 years, 9:08.6 is still the second-fastest 3,000 ever by a high school girl outdoors, after the 9:00.62 record set by Katie Rainsberger of Colorado while placing seventh in the 2016 World Junior meet in Poland. (Mary Cain ran 8:58.4 after turning pro while in high school in 2014.) Several girls including Cain and Katelyn Tuohy have run faster than Bjorklund’s mark indoors. Tuohy’s 9:01.81 from 2019 is the indoor record. Bjorklund’s track career ended that summer at 18. Cross-country gave her a temporary lifeline as she tried to break free of health problems. She entered the University of New Mexico for the in-state tuition and repeated as AAU national champion that fall. With it all, as though summoning a reckoning, the ’75 cross-country nationals may have been Bjorklund’s best race ever. On Thanksgiving weekend, in Belmont, California, Bjorklund ran the rolling three-mile course in 16:24 to defeat reigning world champion Julie Brown by 20 seconds. “I was scared of everybody — the girls back East. Just everybody,” Bjorklund told the media afterwards. That didn’t sound like Bjorklund. Didn’t the prized Russian urn provide a mantle of the sages, words from Chekhov echoing from its mouth like the mystical message of a seashell? Besides, no one from “back East” was a contender or wound up in the top ten. Lynn could not summon the details, but her lapse in confidence likely stemmed from leg injuries, as I learned, that caused her to drop out of all three of her races prior to nationals that fall. Lynn’s large caloric deficit — more energy expended than taken in — which resulted in lack of menstruation and low body fat (now called RED-S), likely prevented the production of the hormone estrogen, essential in bone building. This is often the reason why high school phenoms are prone to stress fractures. How could Lynn’s body hold up? Was it sheer will, the will of the Jemez? What Bjorklund could remember was that when the AAU again refused to pay qualifying women’s trips to the world cross-country — this time for Chepstow, Wales, in February, 1976 — the good people of Los Alamos raised the funds to help support her travels. The citizenry came up with $850, Lynn’s parents chipped in some more, and the “Los Alamos Legend,” as she was now being called, was on her way. Bjorklund looked forward to seeing the sights, going to London on a side trip and making friends. The championship race itself? Eh. With her recent injuries, she said, she didn’t expect much on the race course. She got her fill in the hotel room. Joining Lynn were two pioneering veterans. One was the five-time world cross-country champion Doris Brown (later Doris Brown Heritage) — she won the first five ever held (1967 through 1971); and, for overcoming gender barriers and sexism to create a path for others, DBH, now 80, was to running what RBG would be to the law. The other woman was Cheryl Bridges, who would become Cheryl Flanagan and better known for her daughter — the New York City Marathon champion and Olympic medalist Shalane Flanagan. Brown and Bridges had scraped up some funding of their own. “The three of us roomed together to save money,” said Bjorklund. The room had two beds. Not to worry. Brown, 33, the den mother of the trio, volunteered to sleep in the bathtub, a proven efficiency she had come up with on past trips. When I reached DBH at home in Stanford, Washington (she’s a lifelong Washingtonian) to check on the particulars, Heritage told me, it was no problem, “I always slept on hard surfaces.” Heritage, who years earlier ran a world record 4:52.0 indoor mile, had also learned how to manage the women’s financial predicament. On earlier trips, she took out bank loans. For Chepstow, she set out jars around her small community, inviting donations for the local hero to represent the United States yet again — a world champion not given a dime by the AAU, known to indulge its blue blood bigwigs with silver service travel. She called her campaign, “Dimes For Doris.” The dimes piled up, and DBH was headed to the airport, as long as she could find two roommates, like college kids traveling abroad on five dollars a day.

Women were just glad “to have a race,” a championship, and to meet people and see a bit of the world, she said. Pressed on how the AAU treated young women in general, she replied, “Not very well. I’ve put it out of my mind. It’s too painful.” Bjorklund was right — she wouldn’t run up to speed. But it was still pretty good: seventh place, first American woman, in 17:02 for 4,800 meters, about three miles, leading the U.S. squad to the bronze medal. Heritage was next for the U.S. in 19th, at 17:17. Bridges placed 38th. Victory went to Carmen Valero of Spain, 22, in 16:20; she would triumph again in ’77. The silver medal was taken by Tatyana Kazankina, 24, of the Soviet Union, who would set seven world records including a 3:52.47 1500, and win three Olympic gold medals. Her career ended abruptly in 1984 when she was suspended for 18 months for refusing a drug test after winning a race in Paris. Oftentimes, a shattering trauma from childhood carries lasting burdens. After the world cross, as Bjorklund entered the next stage of life, she still had demons to confront. Even with friendships made and the sweetness of camaraderie from no less than the Russians, Lynn was again alone with herself and coping with a haunting despair. She would continue on a parallel path: running in the mountains for “survival” — a word she would repeat when we spoke — and navigating the outside world wherever she could find comfort. “My time in the wilderness kept me alive,” she told me in no uncertain terms. To be “alive” was one thing, to acquire healing and health another. When, if ever, would Lynn find contentment, peace of mind, and be able to put the hurtful past behind her? Even though her U-New Mexico coach had called her “the best prospect at her age I’ve ever seen,” Lynn transferred after her freshman year to Seattle Pacific. Heritage was on the Falcons’ coaching staff and engineered a full scholarship for Lynn, who looked forward to her new coach’s mentoring. Soon after entering SPU, Bjorklund took her mountain immersion to the ultimate. She raced the ascent division of the Pikes Peak Marathon in Colorado. At last, her ideal distance and course, reaching a zenith of 14,115 feet. For the 13.3-mile climb, gaining 6,300 feet of altitude at an average grade of 11 percent, Bjorklund established a women’s ascent course record of 2 hours 44 minutes that would stand for 46 years. “I just jumped in,” she said. “It was fun.” Poor nutrition, injuries, trauma — and running Pikes Peak? It didn’t add up. But Pikes Peak was another healing balm. Drape yourself in God’s country for a few hours of relentless work, up, up, to the sky, let those endorphins run wild, and throw all the psychic wounds in the slush pile. Bjorklund knew her place. “You’re by yourself in the wild. You don’t expect anything. No one can hurt you,” she offered. Soon, Bjorklund’s injuries emerged in full. She couldn’t run for Seattle Pacific, felt guilty about taking scholarship money, departed the Northwest and went to her third college, New Mexico State, on an academic scholarship. Lynn couldn’t compete for the Aggies either. But she got a B.S. degree with a double major and, then, some years later in 1985, a master of science as well, all pointing toward her career in the natural landscape. Bjorklund then put her science background to use by paying her company town dues at the Lab for an eight-year employment stint, did some seasonal work with the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture and then did four years with a microbiology firm. Lynn continued running when her injuries allowed, giving relief to her disquiet heart. “Recovery was gradual,” she said. At one point, Bjorklund went to Alcoholics Anonymous even though she didn’t drink. She wanted to follow the 12-step program and, she said, “I knew that any kind of community helps.” She was always most at home with the community of adventurous runners from pure stock like herself. In 1981, Lynn had returned to Pikes Peak to contest the full marathon, up and down. She ran 4:15:18 to set a women’s record that would stand for 31 years. More turbulence out the window. In 1990, Bjorklund sought solace in a new locale. She up and left Los Alamos for a comparable oasis in the old mining town of Ely, Nevada, where she got a job with the Bureau of Land Management of the Department of Interior. She was a natural resource specialist in mining reclamation. Her work in part: “Getting plants to grow in impossible places.” She ran in the White Pine Range in eastern Nevada. At times, Lynn was able to run trail endurance races on a whim with friends. Runs in which you ran up to a ridgeline, climbed cliffs and needed spotters on the way down to make sure no one toppled to their deaths. Around the time she turned 40, in 1997, Bjorklund almost singlehandedly prevented two deaths on a hiking-and-camping trip in the Pecos Wilderness near Los Alamos with her other older brother, Eric, and her sidekick, a Belgium Terverun named Toulouser. Mark was supposed to join them — the three siblings have remained close — but was having shoulder surgery at the time. Had he done so, as a physician, he would have had his cell phone with him. Lynn and Eric, holding to wilderness ethos, did not. In an episode that would become local legend — and celebrated in 2022 on its 25th anniversary — after Lynn and Eric saw a light plane go down in the distance and catch fire, Lynn proceeded to run three hours, 18 miles, through the primitive trails to find a home with a cell phone and call for help. “I knew every single trail and also had many years of safety and rescue training,” Lynn said. Her call resulted in two helicopters rushed to the crash site. The injured men were still alive and airlifted to a burn center. They survived. Naturally, Lynn refused any status as hero. But she did find contentment in the consequences of her rescue run, as though her thousands of hours in the wilderness had a greater purpose and led to this moment. After all the AAU titles and records, the big races and big trips, Pikes Peak up, down and sideways, she could say, “This was the most meaningful run of my life.”

In 2010, Bjorklund returned to Los Alamos, starting her current position as recreation specialist with the Espanola District of the Santa Fe National Forest. As of today, Lynn had almost 35 years with the federal government, perhaps an unlikely alliance for such an independent thinker. But she had to get her fingernails dirty, and what better way than by helping to protect our most basic life source — the land. In time, the land worked its wonders and Bjorklund got better. No drugs or therapy, just, she said, “being in the wilds by myself for months at a time.” Time heals. God clarifies. “The wilderness took away all the stress of trying to survive in a world where I had not learned to survive very well.” Perhaps Lynn’s perseverance stemmed in part from her Finnish heritage and the concept of Sisu, said to have infused the likes of Paavo Nurmi, Lasse Viren and others with a strength of will and courage to overcome adversity. In the early 1900s, Bjorklund’s grandmother came to Michigan from Finland, where her parents had sold her as an indentured servant. She married and started the branches of the family tree in the U.S. After moving to Los Alamos for Lynn’s father’s position at the Lab, her mother, Marilyn, became a teacher of botany and birds, with a love of nature she would pass on to her daughter. Lynn still runs every day for hours. When the snow is abundant, as it was this winter, she cross-country skis. She’s found the harmony to feel okay. Her work in the forest includes course approval for trail races, trail upkeep and anticipating and dealing with forest closures due to fire danger. She’ll run some of the races herself. But last year she jumped into a sprint, a 5k. It was one of those prediction runs in which you guess your finish time. Lynn — remember, she’s 65 —guessed 24 minutes even. Her time: 24:00. As with so much else in her running, Lynn won, without winning as a goal. Without, as she saw it, the blemish of vanity. In 2018, in a show of recognition that at one time would have embarrassed her, Bjorklund was among the first athletes chosen for induction into the High School Track and Field Hall of Fame. She was in a group of 25 including Jesse Owens, Bob Mathias, Steve Prefontaine, Gerry Lindgren and Mary Decker Slaney. Lynn traveled from Los Alamos with brother Mark as her guest to attend the ceremonies at the New York Athletic Club. They ran in Central Park and got lost. What did you expect from two runners who knew every inch of the Jemez but got disoriented on concrete? At one time, the NYAC forbade female members but the club finally relented in 1989. Lynn could claim some role in that, with a precious legacy that began in her teens with the junior cross country victory over Decker, and grew in abundance as women runners sought the freedoms that were rightfully theirs. Honors for achievements in high school: Lynn Bjorklund deserved the attention after all. The finish line was always waiting for her. # Marc Bloom’s personal reflections on track and field and cross-country history appear periodically. Marc’s latest book, “Amazing Racers: The Story of America’s Greatest Running Team and Its Revolutionary Coach,” about the Fayetteville-Manlius cross-country dynasty, was named 2020 Book of the Year by the Track & Field Writers of America. Last fall, Marc was inducted into the new Van Cortlandt Park Cross Country Hall of Fame. More news |

Once in Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, Bjorklund felt no burden of international drama, only to run with the same innocence of that first mile when she was a darkhorse in borrowed spikes.

Once in Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, Bjorklund felt no burden of international drama, only to run with the same innocence of that first mile when she was a darkhorse in borrowed spikes. And then Lynn was shown the ultimate respect with the presentation of a special gift bestowed upon her and only her — a decorative urn (see photo), a work of pottery, considered a symbol of Russian hospitality. She still has it, “on a counter with the special things in my life.”

And then Lynn was shown the ultimate respect with the presentation of a special gift bestowed upon her and only her — a decorative urn (see photo), a work of pottery, considered a symbol of Russian hospitality. She still has it, “on a counter with the special things in my life.” Alamos by those who’d looked over their shoulders and saw her, still there.

Alamos by those who’d looked over their shoulders and saw her, still there. Despite the misogyny, Heritage (left) tried to put a good face on things, just as she once did as a young teacher not allowed to enter the school building after a morning run in her workout clothes.

Despite the misogyny, Heritage (left) tried to put a good face on things, just as she once did as a young teacher not allowed to enter the school building after a morning run in her workout clothes.