Folders |

Story of the Stick: Following The Journey Of Penn's Iconic BatonsPublished by

From One Hand To Another, They Arrive At The Penn Relays Carnival Ready To Be Passed, Retrieved, And Passed Again

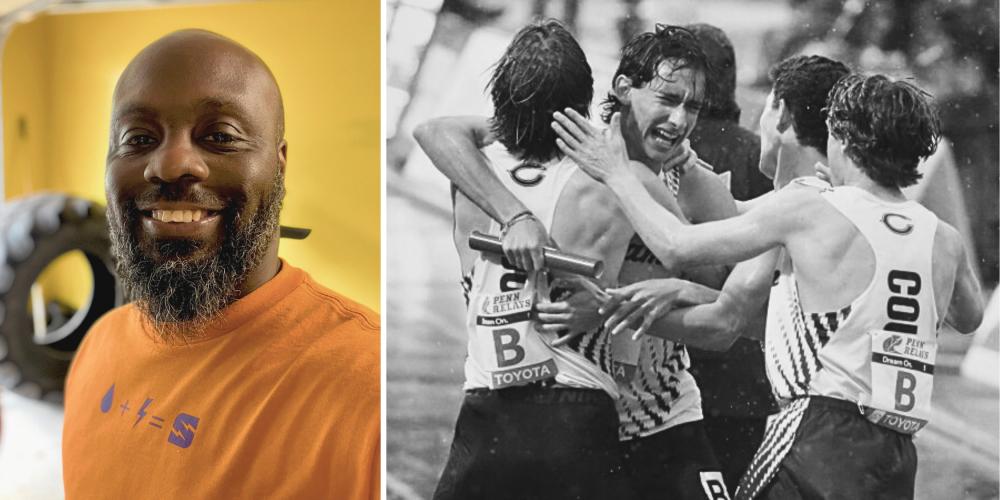

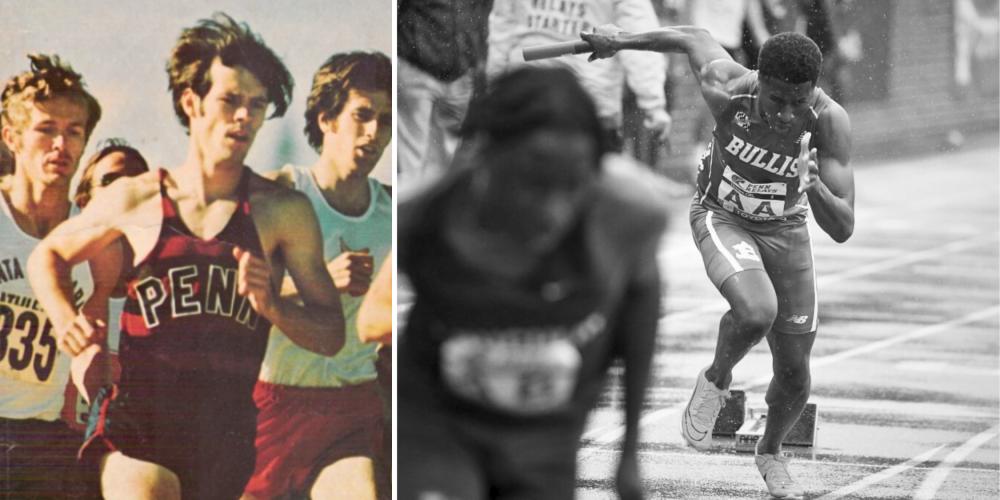

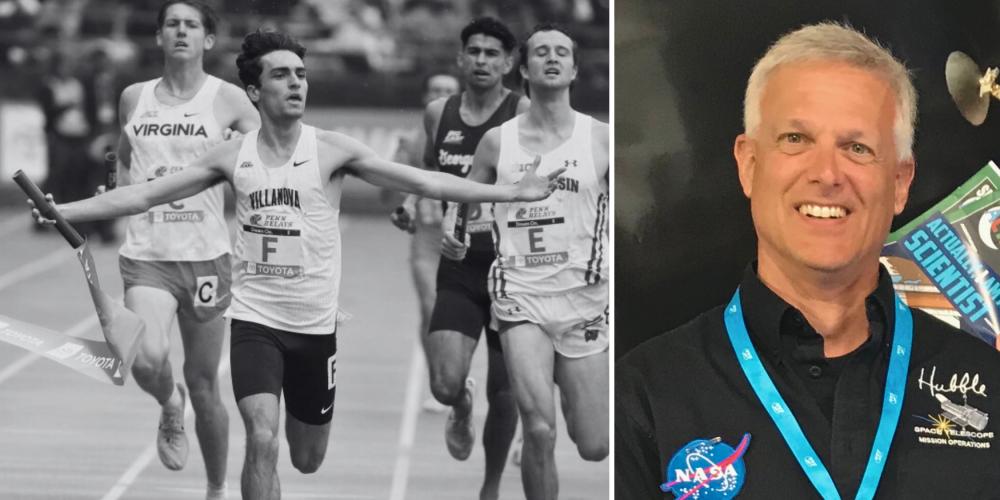

A DyeStat story by Dave Devine Black and white photos by John Nepolitan Others courtesy Penn Relays, Joseph White, Dallas Alexander, Penn Athletics, Jim Jeletic and Jannie Rosado ___________________ Stop the tape, right…there. Freeze it, just as the anchor crosses the line. See that celebration? That exuberance? That’s what winning a Championship of America at the Penn Relays looks like. Pure bliss. Head back, eyes closed, arms extended. Finish line tape fluttering, baton pointed to the sky. Now zoom in on the baton. That iconic red-and-blue stick. How many teams have carried that baton, or one like it, to victory at the Penn Relays? How many hands have held that baton on any given carnival weekend? It’s hard to know, but what if we could hit rewind on this relay. Pull the baton back down from the sky. Pull the arms back in, chin level, finish tape unfluttered and taut again. Make the runners head backwards up the homestretch. Watch their faces go from strained to relaxed. Reeling clockwise around the oval. What if we could scroll backwards — yes, from the anchor leg to the third leg, from the second to the first, but even further back than that. Back before this team was given this baton by the clerks. Back to the previous relay that used this baton. And the one before it. Back even further, to when the batons arrived at the stadium. What if we could rewind back to when they were made. Where would that be? How many hands have these batons passed through? Who got them here? Who held them first? What if we could find out? The Leadoff Man It’s hard to say whose fault it was, all these years later. Did Joseph White blow the handoff? Come in too hot, fail to complete the exchange? Or did his buddy Isaac take off too fast? Wrap his fingers wrong? Fumble the stick? Tough to know; it’s been almost 25 years. There would almost certainly be arguments, old friends laughing and jawing over fuzzy memories. This wasn’t the Penn Relays, it was summer track in the South. The only thing White knows for sure is that roughly 10 seconds into his team’s 4x100, the baton landed in the one place it should never be during a relay race. On the track. And the other teams were streaming away down the backstretch. “I had to run and get the baton before it got to the next lane,” White remembers, “which I did, and I gave it off to Isaac.” The crew from East Point, Georgia, was fast — AAU national qualifiers in the past. They closed the gap quickly, eventually clawing into the top four. But White, the speedy leadoff man, the guy who would be named Most Athletic in his Tri-Cities High School yearbook, has never forgotten that botched exchange. Not because of the mistake, but because of the resilience. “It always stuck with me,” he says, “how we didn’t give up. How I got the baton back, handed it off, and we kept going.” In some ways, that’s a metaphor for White’s entire life. At Tri-Cities, a suburban Atlanta school best known as the alma mater of Outkast members Big Boi and André 3000, White mostly saw himself as an athlete, but he ended up finding his future in a graphic design class. One of the final projects was to design a t-shirt, and for a senior who had always been inventive with his athletic gear — “I was the kid that wanted to spray paint my spikes, always trying to do something cool,” — the intersection of design, sports and apparel opened a window. “I was inspired by that project,” White says, “But I couldn’t draw, man, so thankfully they had Photoshop — if you’re creative you can figure it out.” He earned an associate degree in graphic design from Atlanta’s Bauder College, and has been working in the field ever since. Early on, he learned a process called “sublimation,” in which a design is first printed onto special transfer paper, then applied to a product and heated at high temperatures, turning the ink from a solid to gas, and directly dyeing the underlying material. The result is a permanent, vibrant print that doesn’t fade, crack or peel over time. It’s most commonly used for apparel, but White — an inveterate tinkerer — was keen to try sublimation on other athletic products. His first attempt was baseball bats. After some research and experimentation, he concluded that bats were too big to fit into the home oven he was using as a heat press. And he didn’t have the money to purchase one of the larger, custom ovens necessary to accommodate the Louisville Sluggers. And then an idea hit, from his high school days. “I was like, ‘Hold up — a track baton.’ Because it could fit in a conventional oven.” The early trials, carried out in the family kitchen, were somewhat disastrous. “They were really bad,” White says. “We couldn’t get it right. I was scrubbing them, trying to get the paper off…you’ve got to get your timing down...” Eventually, with help from colleagues, he worked out the kinks. “Over the years we perfected it,” he says, chuckling at the modest start. “It all happened right there in the house.” That was about 13 years ago. At the time, the business he’d launched from his garage with his wife, Tauheedah, was called Athlete Dream. But despite the hopeful name, things were tenuous in the household. Money was tight. They were caring for Joseph’s ill grandmother. They’d just had an infant daughter, named Adisa. And during the pregnancy, Tauheedah had been diagnosed with cardiomyopathy, a heart condition which meant she could no longer continue working in the local school district. It was all-in on Athlete Dream. Over the next decade, the couple endured many of the ups and downs that small, family-owned businesses experience. Big successes, like an apparel deal with the New York Jets and an order from NFL star Alvin Kamara, and withering disappointments, like an investment plan that fell through in the early days of the COVID pandemic. And the baton project? It was mostly sidelined, finding marginal success at the high school level, but dogged by doubts about the vibrant designs — “people thought it was stickers” — and concerns about state regulations. But when the investment plan crumbled, the Whites rebranded as Sports Veins and devoted even more energy to the batons. Among their initiatives was a pitch to equipment supplier Gill Athletics. In the end, the deal failed to materialize, but Gill rep Mike Cunningham was so impressed with White’s hustle and personality that he promised to stay in touch and make some introductions down the road. A year later, White received an email: Joseph, meet Aaron at Penn Relays “Aaron” is Aaron Robison, associate director of the Penn Relays. In 2022, Robison was seeking a less expensive and more durable alternative to the batons Penn had been using for years. Cunningham steered him toward White. After one Zoom-call demo, Robison was sold. Sports Veins’ sublimation batons debuted at the 2023 Penn Relays — in a rainstorm. Ever the optimist, White saw it as a blessing. Robison had remarked that in the past, the Relays had issues with rain; during downpours, the baton ink would leave a residue on runners’ hands. “It was such a great moment for us,” White says, laughing. “Even when it rains, they don’t have to worry about the ink coming off. For a small business, that was major for us.” This year, the Penn Relays have more than doubled their order. There are plans to sell additional customized batons as souvenirs throughout the weekend. It’s a big moment, but Sports Veins remains very much a family business. Joseph and Tauheedah complete most of the design, layout and production work. Much of that still happens in the garage. For big projects, like the Penn Relays, they bring Joseph’s mom, Pam, and mother-in-law, Wanda, on board. And that infant daughter, Adisa? She’s a teenager now, in charge of boxing the batons and sending them off to Philly. “You know how people say, ‘Why not me?’” Joseph muses. “Well, it can be you, you’ve just got to keep on going. You’ve got to keep pushing...” Which brings him back to that fumbled exchange, all those years ago. Even now, he’s still running leadoff. Joseph White and his family — first hands to touch the Penn Relays batons. And those old lessons still resonate: Not giving up. Scrambling to salvage the situation. Figuring out a way forward. “This right here?” White says, “It’s definitely a keep-pushing story.” The Coach’s Kid It’s not accurate to say that Dallas Alexander was raised at Franklin Field. He wasn’t. But for three days every April during most of his childhood, he became something of a temporary resident in the cavernous old stadium. Alexander’s father, Charles “Cake” Alexander, was the longtime track and field coach at Philadelphia’s Temple University. Every year, on the last weekend of April, young Dallas would join his dad and the Owls team for long days in the stadium bleachers. He remembers those weekends, as most kids would, being alternately thrilling and tedious. Recalls the freedom to roam the stadium’s sunny upper deck, and maneuvering the claustrophobic passages beneath the stands. The scent of funnel cake and the stench of Ben-Gay. The beautiful, warm days, and the challenge of being exposed to the cold all afternoon. “I always made the pilgrimage down,” Alexander says. “As a child, you were kind of captive there all day. And not totally getting everything. But as I got older I was able to see everything and understand it more.” Those annual visits made enough of an impression that shortly after graduating from Dartmouth College in 2002, Alexander returned to Franklin Field as a Relays official. If he was known, at first, for being Cake Alexander’s kid, he’s more than carved out his own reputation over the last two decades. Today, he’s the chief marshal for the Relays. It means, among quite a few other things, that Alexander is responsible for distributing and collecting the batons each day. He’s leg two, if you will. Receiving the hand-off from the White family. After being packaged and shipped by Adisa down in Georgia, the batons typically remain boxed in Robison’s office until meet week. On the opening Thursday, Alexander retrieves them from either Robison’s office or the other likely storage spot — a room inside Penn’s legendary Palestra basketball arena. “They usually start down there,” Alexander says, “in the belly of the Palestra.” He counts out a predetermined number of batons and places them in the plastic bin that will house them for the next three days. And how many batons do the Penn Relays require? “Let’s see if I’ve got that…” Alexander says, consulting a Google doc on his phone. “Let me just type ‘B-A-T-O-N-S’ in here…yup! For the 4x800 on Day 1 we start with 43, and — I’ve also got the rates on how long we retain that number…” Alexander pulls up baton-count records stretching back to 2013. He reports an average loss of 22.3% of the batons over six years. The 2015 edition was particularly grim — a 29% disappearance rate. But, he reports brightly, they’ve been improving every year since. “Sometimes the kids absent-mindedly hold onto them,” he says. “The baton is part of the journey. Most of the time we recover them, but sometimes they grow legs and walk off.” His marshaling team is responsible for moving athletes around the field, pulling legs off the track as they finish, and collecting batons at the conclusion of each race — either from completed anchors or exchange zone drops. He circulates every few hours to check inventory, update his Google doc, and assess the need for any additional batons. Occasionally, Alexander glances up from his errands long enough to catch a moment — an electrifying backstretch battle or a Woot-worthy homestretch walk-down — that transports him back to the thrilling Relays he attended as a child. His favorite memory, however, came during his time as a marshal. “The one that really stands out,” he says, “the one I was immersed in, was when Usain Bolt came in 2010.” He was on the infield for that one, his view mostly obscured by hundreds of others who remained on the turf for the show-stopping 4x100. “You know when you’re at a concert,” Alexander says, “and it’s like — it’s the rush of being in a space and sharing a unique and special experience with so many people?” There were 60,000 fans in the bleachers that Saturday afternoon. The announcer had to twice implore the crowd for quiet at the start. The moment the gun went off, the entire stadium surged forward. “I could feel the reverberation inside my body,” Alexander recalls. He lost sight of Bolt once the Jamaican star got the stick, but remembers being able to physically feel the final 50 meters of the race. “It was like a flow of energy,” he says, “the wave that followed the baton around the oval. And once that energy hit Bolt, the potential just kind of surged; you could see that in his speed on the track.” It’s the part of the Penn Relays experience that Alexander can never quite shake — when the roar of the crowd follows the baton around the track. When you know exactly where the runners are in the race, without looking up, based simply on which corner of the stadium is erupting. When sound and speed fuse together. “That,” he says, “is the experience of the Penn Relays that really stands out.” The Sub-4 Miler He wasn’t really supposed to be there, but could you blame him? Karl Thornton, a recent graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, knew better than most that after you finished a Penn Relays race you were expected to clear the track and exit the infield as quickly as possible. On carnival weekend at Franklin Field, there’s little patience for lingering. But Thornton, less than two years removed from his own undergraduate days as a Quaker, had just run the race of his life in front of 38,000 roaring fans at the 1974 edition of the Relays. He was spent, but satisfied. Stunned at the strength he’d found to charge so far under four minutes. And so, trading on his familiarity with the local officials, Thornton reclined on the sun-warmed grass, watched the meet swirl on around him, and soaked it all in. “I was fortunate to get into that race,” Thornton recalls now. “It was really an excellent field.” Thornton and Penn’s then-senior, Denis Fikes, had the raucous support of the partisan crowd. But they were significant underdogs to Tony Waldrop, the lanky North Carolina distance star who’d reeled off seven straight sub-four efforts that winter, including a world indoor record of 3:55. Competing on a gorgeous April afternoon, what the New York Times would later call “perfect racing conditions,” Waldrop outkicked Fikes for a Penn Relays record 3:53.2. It made him the second-fastest American miler at the time, behind only Jim Ryun. Fikes, later known as Denis Elton Cochran-Fikes, finished second in 3:55.0, then the fastest performance ever by an African-American miler. Ray Smedley, a British Olympian, was third in 3:57.7, barely edging out Thornton’s 3:57.9 stunner. Kenya’s Wilson Waigwa also dipped under four, making five in the race. In the year-end rankings, Thornton would sit at eighteenth in the world. Fifty years later, he mostly recalls the feeling he had after the race. How the Penn fans in the south stands continued to roar for him and Fikes. The lactic acid in his legs. The warmth of that grass. The luxury of lingering on the infield long after his effort had ended. “It was nice being a hometown guy that day,” Thornton says. “I knew so many people that let me hang out, talk to friends and just enjoy the moment. It’s unusual, because one of the things we have to do is shuffle all of the athletes right back out.” By “we,” Thornton means the crew of red-capped Penn Relays officials who ensure the sprawling, three-day meet runs efficiently. He’s been part of that crew, in one way or another, for 47 years. From 1979 to 1981, Thornton returned as head coach of the Penn harriers, a position which saw him deeply involved in staging the annual carnival. But even after entering the private sector for a series of jobs in information technologies, he’s made the annual trip to Franklin Field every April to join the clerking crew. These days, he helps orchestrate a process that begins in an alley outside the stadium and extends all the way to the finish line. “The clerks cover everything,” he says, “from bringing the teams off the street and into the stadium, then into the paddock area where the races and sections are separated out.” Thornton and a small cadre of fellow clerks sit above that paddock fray, using microphones and speakers to administer final instructions to the athletes milling below. “We try to be as respectful as we can to the athletes,” he says, “making it as good of an experience as possible. But some of the younger kids are in such awe of where there are, of being in front of so many people, that it’s like they lose consciousness. They’re not hearing you, they’re not paying any attention…” But the mantra of the Penn Relays still holds: Keep them moving. “We have something like 20 or 30 seconds,” he says, “between the finish of a race and the start of the next section.” While Thornton no longer hands physical batons to relay runners, he’s intricately involved in the momentum of keeping those batons in motion around the track — and through the weekend. Asked for his favorite memory in nearly five decades of officiating the Relays, Thornton has a ready response: the University of Pennsylvania women’s victory in the 2019 distance relay medley Championship of America. “That was just spectacular,” he says. His own sub-4 on a perfect Saturday in 1974 would almost certainly be a close second, but Thornton is too modest to mention it. “It was very, very rewarding,” is the most he’ll say. He never broke four minutes in another mile race. And 50 years later, Waldrop’s 3:53.2 is still the Penn Relays’ record. This year, American indoor and outdoor mile record holder Yared Nuguse is coming to town, along with On teammate and Australian star Ollie Hoare, to challenge the mark. If the record goes down, one of the participants from that 1974 race will surely be watching from his perch above the paddock, glancing up from his microphone and the milling runners to witness some Franklin Field magic once again. The NASA Engineer As a child growing up in the suburbs of Pittsburgh, Jim Jeletic would stare up at the night sky, marveling at the stars. He couldn’t have known, or didn’t have the words back then to describe, exactly what he was seeing. Couldn’t have imagined — at the age of 7, when he watched the Apollo moon landing on his family’s grainy television — that in the simple act of squinting at those distant scintillas of light, he was looking back in time. Observing the stars as they appeared millennia ago. Seeing into the past. He was also, unknowingly, glimpsing his future. “As a kid, what I wanted to do was explore the universe and see the things we’d never seen before,” Jeletic says now, “And Hubble allows me to do that.” A 1984 graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, with a degree in computer science and engineering, Jeletic began working for NASA immediately after graduation. He spent more than a decade on the flight dynamics team before joining the Hubble Space Telescope mission in 1998. He’s now the deputy project manager, handling everything from day-to-day mission operations to communications and public outreach. Even after 25 years on the project, he still finds the process of analyzing the images returned from the telescope — the basic, “What is that?” questions that arise — as exhilarating as when he first started with the Hubble unit. And while he might bring an engineer’s intellect to those investigations, he’s also regularly stunned by the sheer beauty of the images Hubble sends back. One of his personal favorites is the image perhaps most widely associated with the space telescope, an assemblage of exposures known as The Hubble Deep Field. Creating that image, Jeletic says, involved photographing a segment of sky so minute, “it’s like looking through the eye of a sewing needle held at arm’s length. Just a really small area of the sky, where we didn’t think there was anything.” It was controversial at the time, because “Hubble time is precious,” Jeletic says — meaning expensive. Dedicating 10 days of observation time to this seemingly insignificant sliver of sky, collecting light from a spot expected to hold nothing, seemed excessive at best, wasteful at worst. “When we were done,” Jeletic says, “we found 3,000 galaxies.” Many of those galaxies are among the youngest and most distant ever observed. It’s a glimpse into the universe’s earliest, most formative days. And for Jeletic, it induced the kind of awe he experienced as a child staring up at those Pittsburgh night skies. Some of the most formative days in his life took place on the University of Pennsylvania campus, where, in addition to his engineering pursuits, he was a walk-on distance runner for the Quakers. His freshman year overlapped with the time that Karl Thornton was the head coach; it was Thornton who first recruited Jeletic to begin assisting at the Penn Relays. The eventual engineer was a student volunteer back then, hustling second and third legs from the 4x100 out to their respective exchange zones. At the end of the three-day shift, the former coach asked Jeletic, then a senior, if he’d ever consider becoming an official. The next spring, Jeletic joined Thornton’s clerking crew. He’s been there for the last weekend in April — save two COVID-cancelled years — ever since. He now serves as the head of starting line clerks, a role he inherited when Thornton ascended to the rows above the paddock. When the relays are dispatched from that paddock out to the track, Jeletic’s team ensures all the squads are present, no members are missing. And it’s there, along the brick wall leading to the starting line, that the leadoff runners receive their batons. “Sometimes kids come with their own batons,” Jeletic says, “and we explain to them that this is the Penn Relays, you get to use a Penn Relays baton.” Nearly every leadoff runner eventually meets the NASA engineer. “I’m out on the track, physically putting them on the starting line,” he says. “You’re standing here, you’re standing there, move a little to your left…that type of thing. And then giving them their final instructions.” He doesn’t typically distribute batons, but he always keeps an extra in his back pocket. “For the inevitable runner that I’ve moved to the starting line,” he says, “and the starter shouts, ‘On your marks…’ and the kid screams, ‘I don’t have a baton!’” Jeletic laughs, amazed at how often it happens. “You always wonder, ‘How did you not get a baton? Literally everybody around you has one.’” But in those moments, with the leadoff runner starting to panic, it’s Jeletic, with the measured tone and even-keeled approach that has served him throughout his career, who gets to restore calm to the situation. He produces the baton from his back pocket, almost like an act of prestidigitation, and makes, for that team, the most important handoff of the day. The P.E. Teacher In the summer of 1990, Jannie Rosado experienced two things that would change the course of her life. One was catastrophic, the other avocational. A recent graduate of DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, Rosado was riding one of the familiar New York rail lines when her train abruptly crashed. Maintenance workers had left debris on the rails. “It caused the train to partially derail,” Rosado recalls, “and I went flying forward.” Caroming through the train car, she was left with a fractured bone in her neck and a badly injured back. It meant that Rosado, who had been a sprinter at DeWitt Clinton, a youth track star since she was 5 years old, could no longer pursue the sport she loved in college. After a summer of recovery and rehab, she was able to start classes at St. John’s University on time, but her track and field days were over. Or so she thought. Fortuitously, Rosado’s longtime club coach also happened to be the commissioner of officials for girls track in the area. The same summer as her accident, the coach pitched her on helping out at track meets as a way to earn spending money. “Right out of high school,” Rosado says, “he was like, ‘Hey, here’s a way to make some change on the side and help pay for your college books.’” Thirty-four years later, that initial, encouraging conversation has spun into a lifetime of opportunities for Rosado as a highly-regarded track and field official. “I’m all over the place,” she says, rattling off events in the Bronx, a public school league in Manhattan, commitments with the New York Catholic schools, Independents, Ivy League universities, NCAA — “I do it all.” Perhaps most prominently, Rosado is the coordinator of officials for The Nike Track and Field Center at the Armory in New York’s Washington Heights. For a self-described “girl from the Bronx,” who got her start competing in club track at the Colgate Games, it’s been a precipitous rise. The eighth of nine Rosado children, Jannie’s competitiveness was stoked by family races with her older brothers and sisters. As a kindergartener, her P.E. teacher identified her as precociously talented. Soon, she was training with the same coach who eventually steered her towards officiating. At DeWitt Clinton she ran everything from the 100-meter dash to the 400, plus plenty of relay carries in between. “The coaches we had back then, and the way things were,” she laughs, “we ran what we were told to run.” An annual highlight was the team’s trip to the Penn Relays, where Rosado remembers the atmosphere more than the actual races. The chance to stroll around the massive stadium with her friends. Meet kids from other teams. Purchase things at the vendor booths. When she works the Relays now, there’s little time for those diversions. Rosado is one of the marshals for the meet, responsible for ushering relay teams and individual runners on and off the track as quickly and safely as possible. For the majority of the packed schedule, she works near the finish line, but during the 4x100 heats she’s stationed at what she calls the “hot zone”: the first exchange zone, between legs one and two. Her responsibility isn’t only to shepherd athletes; she plays a pivotal role in ensuring the flow of the batons throughout the meet. “We watch the baton make it around the track,” Rosado says, “and those that don’t — well, it’s our job to make sure we retrieve them. Because they’re a hot commodity, and they will disappear. And that ‘hot zone’ is where a lot of batons get dropped with missed exchanges.” Rosado estimates that in the 4x100 heats alone, she might end up returning 15 to 20 batons to the collection bin. “I’ll wait until everyone in that zone has exchanged,” she says, “then I’ll race out and grab it.” She returns them to the bin at the finish area, another pair of hands for the batons to pass through on the long weekend relay. She’s an educator and a coach herself these days, has been for years. She’s covered a variety of subjects and grades, but now teaches physical education. Kindergarten through eighth grade at a school in the Bronx. Just like that P.E. teacher who first noticed her as a 5-year-old. The one who connected her with a club coach, who connected her with officiating. “It’s definitely nostalgia,” Rosado says, thinking back to her younger self. The DeWitt Clinton sprinter who ripped around Franklin Field every April. “Like, wow, I can’t believe I ran this meet. This doesn’t look as big as it did when I ran. But I remember this turn, that wall, holding these blue and red batons…” More news |